- Home

- Stanley Donwood

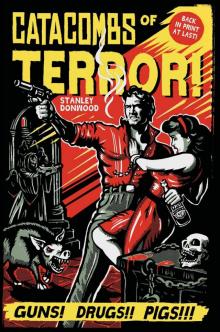

Catacombs of Terror!

Catacombs of Terror! Read online

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction

Chapter 1: Death Threats

Chapter 2: Oh Fuck You

Chapter 3: My Stupid Job

Chapter 4: Rather You Than Me

Chapter 5: Low-Rent Philip Marlowe

Chapter 6: Very Strange

Chapter 7: Things Could Only Get Worse

Chapter 8: No Messages

Chapter 9: Wet Handshake

Chapter 10: Shiny New Shoes

Chapter 11: Very Large Drink

Chapter 12: Seriously Bad News

Chapter 13: Biological Weapon

Chapter 14: Where’s My Flashlight?

Chapter 15: Pigs

Chapter 16: Efficient and Decisive

Chapter 17: Basically Very Out to Lunch

Chapter 18: An Interest in Guns

Chapter 19: Fucking Horrible

Chapter 20: Don’t Fucking Panic

Chapter 21: Eyes Wide Open

Chapter 22: Alive with Corruption

Chapter 23: Then You Will Remove Her Head

Chapter 24: Rope

Chapter 25: The End

About the Author

Catacombs of Terror!

Stanley Donwood

[Tyrus Books logo]

[FW logo]

Copyright © 2015 by Stanley Donwood.

Originally published in the United Kingdom.

First U.S. printing, 2016, Tyrus Books.

All rights reserved.

This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher; exceptions are made for brief excerpts used in published reviews.

Published by

TYRUS BOOKS

an imprint of F+W Media, Inc.

10151 Carver Road, Suite 200

Blue Ash, OH 45242. U.S.A.

www.tyrusbooks.com

ISBN 10: 1-4405-9669-7

ISBN 13: 978-1-4405-9669-8

eISBN 10: 1-4405-9670-0

eISBN 13: 978-1-4405-9670-4

Printed in the United States of America.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Donwood, Stanley, author.

Catacombs of terror! / Stanley Donwood.

Blue Ash, OH: Tyrus Books, [2016]

LCCN 2016001979 (print) | LCCN 2016011432 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440596698 (hc) | ISBN 1440596697 (hc) | ISBN 9781440596704 (ebook) | ISBN 1440596700 (ebook)

LCSH: Private investigators--Fiction. | Bath (England)--Fiction. | Detective and mystery fiction.

LCC PR6104.O59 C38 2016 (print) | LCC PR6104.O59 (ebook) | DDC 823/.92--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016001979

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, corporations, institutions, organizations, events, or locales in this novel are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. The resemblance of any character to actual persons (living or dead) is entirely coincidental.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and F+W Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters.

Cover illustration and design by Chris Hopewell (Jacknife Design).

Author photo © Jake Green.

This book is available at quantity discounts for bulk purchases.

For information, please call 1-800-289-0963.

Introduction

The book you hold in your hands should not exist. By rights the manuscript should have taken flame and turned to ashes, high on Solsbury Hill in Somerset. It has a strange and convoluted history, which is only now, more than a decade after it was written, coming to light. If you are willing, I will take you back in time, to the early years of this century.

It was some time during the interminably hot summer of 2003 that I was approached by a publisher called Ambrose Blimfield, who had, he stated, a manuscript that I may be interested in acquiring. At the time I was the owner of an antiquarian bookshop in the city of Bath, and the manuscript, entitled Catacombs of Terror! was, Blimfield told me, set exclusively within and around that city. Rather excitedly, he insisted that the contents of the book would shake Bath to its core, forever demolishing the rather genteel fascination with the novels of Jane Austen then prevailing in the city—if only people could read it.

I was at a loose end, had no pressing engagements, and so I opened a bottle of Bordeaux and invited Blimfield to join me in a glass or two, and to tell me a little about this manuscript.

Catacombs had been written, he told me, as a result of a bet between Blimfield himself and an artist then living locally named Stanley Donwood, a bet laid on the night of the millennium. At the time Blimfield owned a publishing house called Hedonist Press, printing slender volumes of poetry and prose, although financial difficulties had driven him latterly to publish cheap pamphlets of erotica. Donwood had lately accrued some small degree of repute, creating record sleeves for pop groups, and had met Blimfield whilst carousing in one of Bath’s seedier pubs, the Bell in Walcot Street.

Somehow a cider-fuelled bet had been laid between publisher and artist; and Ambrose Blimfield agreed to pay Donwood a handsome royalty if the latter could write a sixty-thousand-word detective novel in one month. The artist accepted, and amazingly, won the bet—Catacombs of Terror! was the result.

As Blimfield forcefully put it, the book was staggering. Set entirely locally, in and around the city of Bath, the novel was indeed a detective novel, a ‘page-turner,’ a ‘blockbuster,’ a ‘gripping, unputdownable’ thriller detailing the exploits of private eye Martin Valpolicella, as he battled through a single weekend of guns, drugs, and pigs. The book also drew heavily on some rather arcane research that Donwood had undertaken, research that hinted at a deeply unsavoury side to the city of Bath. Blimfield conceded that the book’s style was somewhat slapdash, veering into cliché almost continually, sloppily written and falling far short of any conceivable literary merit.

On one hand the book marked a pinnacle of Blimfield’s publishing career, and on the other it finished him off. He never published a book again, and retired bitter and cynical from the book publishing business.

His attempts to promote the book through bookshops, distribution channels, and direct to the public were plagued with disappointment, argument, legal disputes, and were ultimately doomed to almost complete failure.

In the meantime there were production issues with the book itself. The hemp paper that Blimfield insisted on for all his publications had been difficult to procure, and unreliable in use; the printing of Catacombs had been interrupted when the printers discovered sheets with holes in them. The replacement consignment was sound and the books finally printed, but this proved to be the last useable hemp paper ever dispatched from the mill. Its pioneering creator, John Hanson, mysteriously disappeared from his Dorset headquarters shortly afterwards, leaving no forwarding address. And none of the legendary ‘tree-free’ paper either. Blimfield’s repeated attempts to trace him proved fruitless.

The Hedonist Press had lost its source of paper on which to print. While other publishers depended on authors, Blimfield’s operation depended on hemp. He admitted to me that he didn’t mind so much about the content of his books, it was what they were made of that counted. His publishing motto was Hoc Excreta Bovis Possit, Mineme Non Aborious Factum Est (sic), which supposedly translated as ‘It may be bullshit but at least we didn’t cut down any trees.’ With no hemp, only woodpulp material remained, and Blimfield was stuck until someone was making hemp

paper again. And this, in the early years of the twenty-first century, seemed extremely unlikely.

The stock of hemp paper that Blimfield possessed was enough to print a scant one thousand copies of Catacombs, provided that he set the type small and kept the margins narrow. The novel was eventually published in 2002, by which time Stanley Donwood had moved to London to pursue his artistic ambitions. While Internet sales of the books were steady, Blimfield remained disenchanted, occasionally muttering, “A book isn’t a real book until it’s in a bookshop,” and insisting “Oxfam doesn’t count.” Eventually he took the entire remaining stock of the books to the neighbouring city of Bristol to try the retailing opportunities there—but promptly lost them somewhere in the city’s Stokes Croft area.

It was time for Ambrose Blimfield to contact Stanley Donwood. There were no royalties to pay him—the book had actually lost Blimfield a considerable sum—but Blimfield was, by this time, part owner of a cider-apple orchard and decided to pay Donwood in cider. The pair agreed to meet on the top of Solsbury Hill on the outskirts of Bath.

It was at this point in his account that Blimfield began avoiding my eye. His enthusiasm for his tale seemed to wane. But I refilled his glass and gestured for him to continue.

Solsbury Hill rises more than six hundred feet above sea level, and lies to the east of Bath. For Blimfield it was a weary climb on a hot afternoon, carrying a great deal of cider. When he arrived at last at the summit, he saw that Stanley Donwood was already there, leaning against a concrete triangulation point, looking down over the city.

Donwood, it appeared, had not forgotten about Catacombs—far from it. During his sojourn in London he had returned repeatedly to the manuscript, which he now presented once more to Blimfield. He had corrected it, he had edited it, he had made it better. Blimfield told me that he was once again presented with the manuscript of Catacombs of Terror!—a dog-eared ream of A4 pages, stained with coffee, wine, and grime, heavily annotated, with paragraphs crossed out, scrawled handwriting crowding the margins—and yes, from a perfunctory reading of the initial pages, it did indeed seem to be a superior job to the original. The two of them spent several hours drinking cider and smoking marijuana as the sun set over the city of Bath below them, their conversation sometimes turning to the fortune they would make with this rewritten masterpiece, sometimes to the futility of writing, of publishing, of life itself.

They lit a small fire as twilight enveloped the hill. By now they were both quite drunk. Blimfield says that Donwood had fallen silent, merely nodding as the publisher expostulated upon the iniquities of vested interests in the print trade, on the emergence of Amazon, and on the insurmountable difficulties facing those in the book trade. Apparently at some later stage, after stumbling to his feet, Donwood uttered a terrible shriek and threw his precious manuscript into the fire, before collapsing to the ground, insensible.

Blimfield made some attempts to rouse the artist, but received only abuse for his efforts. It was then that his gaze turned to the manuscript smouldering on the fire, flames licking at the dog-eared pages. He made a decision at that moment. With a glance at the snoring Donwood, he seized the burning bundle of papers and pulled it from the fire, patting out the creeping combustion with his bare hands, smacking the manuscript on the grass.

Blimfield told me that he didn’t really know what he was doing, that he couldn’t be held fully responsible for his actions due to the amount of cider they had drunk—but he made the decision that the manuscript could not be lost.

He draped his jacket over the slumbering Donwood, left the remains of the cider next to him, and ‘practically fell’ down the steep side of Solsbury Hill. He claimed to remember nothing of the rest of the night, and was awoken, still clutching the sooty manuscript, the next morning by the cleaner of the Bell in Walcot Street, who asked him what he was doing sleeping in the toilet cubicle.

I asked Blimfield if he had seen Donwood since that night on Solsbury Hill, and he shook his head. The two had exchanged letters, postcards, and the occasional e-mail, but Donwood, having returned to London, had remained under the impression that he had destroyed the only copy of the manuscript of Catacombs of Terror!, that he had thrown it, drunkenly, into a fire. According to Blimfield he had said that it was ‘probably for the best.’ Apparently Donwood had ‘form’ in this sort of behaviour, having destroyed a novel entitled Yobs that he had written on the grounds that it was ‘too violent.’

The manuscript that Blimfield was offering me did fit with the description given. It was of about four hundred sheets of A4, bundled with elastic bands, scorched at the edges, stained, enthusiastically annotated, and entitled Catacombs of Terror! The exclamation mark, said Blimfield, was very important. Blimfield himself had indeed forsaken the world of book publishing, and was now in the newspaper business, and proposed to purchase a decommissioned milk float, in order to travel the country publishing local newspapers, written by an ‘acquaintance’ of his. It was to raise funds for this venture that he wished to sell me the manuscript.

By now our bottle of wine was empty, but Blimfield’s story had intrigued me. I opened another bottle and we began to discuss a price. To be fair, I had no real reason to buy the manuscript, but now I felt that I simply had to read it, and at the time—oh, those balmy days at the start of the century—I was comparatively well off. Of which more shortly. As far as I understood the story, there had been a thousand copies of the first draft of Catacombs published, some of which had been sold, some of which had been lost. There was no electronic copy of the text, the computers belonging to Hedonist Press having long been consigned to landfill. The only extant copy of the manuscript—an edited, corrected version—lay on the desk between us.

That hot afternoon drew on, and Blimfield enthused about his milk float and about the dire need, as he saw it, for genuinely local daily newspapers, and about the ability of his business partner to write these newspapers with very little knowledge of local matters. This new acquaintance, it appeared, was also willing to be paid in cider. I kept my considerable reservations about all of this to myself, and, as the second bottle was finished, we agreed on a price; I paid Blimfield, and, as it happened, that was the last I saw of him. I wished him well with his milk float, his nascent newspaper empire, and thought little of the matter for the next decade. The manuscript, all but forgotten, languished in my desk drawer—until 2014.

• • •

The foregoing is by way of a preamble, some background to explain how you, the reader, happens to be reading Catacombs of Terror! As I say, in 2003 I was the proprietor of a small antiquarian bookshop in Bath—and that was the trade I plied for some years after. I put the manuscript away for safe-keeping, and concentrated on my shop, on buying and selling, on book fairs, rumours of rare first editions, on calfskin bindings, disputed titles verso, on ‘slight foxing’ and ‘signs of wear.’ But to my dismay, the real world, as it likes to be known, came knocking. Publishing houses such as Wordsworth began to print cheap editions of the classics—and thus I lost the casual trade of the students looking for serviceable copies of Shakespeare, Dickens, Thackeray, and the like. Then the Internet began to take chunks from my market—who would browse my dusty shop when they could type in a title on their personal computer and buy the edition they chose from a host of sellers worldwide at the click of a mouse?

The shops that neighboured mine closed one by one, replaced by estate agents and outlets offering overpriced coffee, with ‘boutique pop-ups’ which appeared to sell nothing very much at all. It was a slow process, almost imperceptible, but my shop became untenable. My lifestyle—late rising, a glass of wine or two at lunch, amiable conversations with fellow bibliophiles—became untenable. With great regret, I closed my shop, and announced to my landlord that I would not be renewing my lease.

Whilst engaged in the desultory process of clearing out my shop I came across the—almost forgotten—manuscript that I had bought from the publisher Ambrose Blimfield a full decade previously.

The whole tale came, unbidden, back to me. And I thought to myself—perhaps now is the time to ‘cash in’ on my investment?

One does not run an antiquarian bookshop for twenty-five years or more without making friends, and recently I had been spending some time with a very good friend who shared much of my dismay at the way that things had changed, the way things were not as they used to be, particularly in the world of books.

The publishing house of Scratter & Pomace was founded in 1888 by Alfred Scratter and Juan Pomace, and for many years was highly regarded in the book trade. Notably, the now classic A Pedlar’s Tale by Devlin Crease was published by that house to great acclaim at the turn of the century, and their deftly chosen list was envied by many. During the second half of the twentieth century they fought hard to avoid being subsumed into the great conglomerates, jackals such as HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, and the like.

In hindsight this may have been something of a tactical error, as it turned out that the very same economic forces that brought low my own little shop had also unhorsed the venerable firm of Scratter & Pomace—cheap reprints of out-of-copyright classics, Amazon’s dominance of the market, and so on.

Richard Scratter, the great-grandson of Alfred, was my very good friend. And it was to him that I turned. The glory days of deluxe hardback editions, it was apparent, were in the past. S&P had fallen sufficiently low for them to be competing with the likes of Wordsworth on cheap reprints of Treasure Island, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, and suchlike. Richard was contemplating the fate of other publishers he knew who had been reduced to printing anthologies of what is apparently termed ‘bottle-creep’—amateur erotica reprinted from Internet sources, where like-minded perverts would share and mutually appreciate appallingly written screeds of sexual fantasies.

Scratter and I discussed the possibility of publishing Catacombs of Terror! as a mass-market paperback, and over lunch in a delightful restaurant we made an agreement. He would engage a professional to retype the manuscript, and a highly proficient illustrator to produce cover art, and Catacombs would live again.

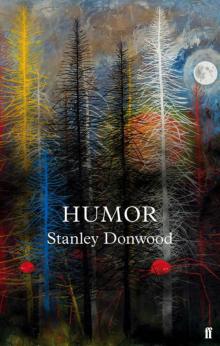

Humor

Humor Catacombs of Terror!

Catacombs of Terror!